“These publications will not cost lives. Who killed people? We are not killing people, I’m sorry. We are not the violent ones. We are just journalists.” —Gerard Biard, editor-in-chief of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo

“So let’s get this straight: In the consensus view of modern American liberalism, it is hilarious to mock Mormons and Mormonism but outrageous to mock Muslims and Islam. Why? Maybe it’s because nobody has ever been harmed, much less killed, making fun of Mormons.” —Bret Stephens, “Muslims, Mormons and Liberals,” The Wall Street Journal

David Freedberg, the Pierre Matisse Professor of the History of Art and Director of the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America at Columbia University, opens his book The Power of Images (1991) with the following assertion:

“People are sexually aroused by pictures and sculptures; they break pictures and sculptures; they mutilate them, kiss them, cry before them, and go on journeys to them; they are calmed by them, stirred by them, and incited to revolt. They give thanks by means of them, expect to be elevated by them, and are moved to the highest levels of empathy and fear. They have always responded in these ways; they still do.”

This is an apt reminder in the wake of the 2012 straight-to-YouTube movie, “Innocence of Muslims,” which, we were repeatedly told by news media outlets, launched an incendiary wave of protests across the radical Muslim world. Only a week later, the French magazine Charlie Hebdo published cartoons featuring the prophet Muhammed in “questionable” postures.

As a precaution to violent outbreaks, France closed embassies and schools in around twenty countries; it also officially banned protests. As a proactive measure to bring to justice what he regarded as a blasphemous movie, a Pakistani railways minister, in a move reminiscent of the Vader/Fett relationship, placed a $100,000 bounty on the head of the filmmaker.

On January 7, 2015, two gunmen stormed the Charlie Hebdo offices and shot and killed twelve people. Afterwards the terrorists reportedly declared, "We have avenged the Prophet Muhammad. We have killed Charlie Hebdo!"

For Americans immersed in an alternate universe to Salafist-styled Islam, it is inconceivable that a filmmaker could be held responsible for the reactions of viewers. “It’s just a movie,” the thinking goes, and the filmmaker presumptively has a right to express his or her views just as the viewers have a right to watch or not to watch the movie.

“Take it or leave it, but you can’t make a filmmaker responsible for a public’s response.”

That’s the gist of the American reaction to the demand of pro-Al Qaeda Muslims that the U.S. government punish the filmmaker, preferably by execution.

To Americans, the notion that a filmmaker could injure an entire country or people group is not only incomprehensible, it’s also irritating. If you watched the Facebook posts around the time of the political ruckus, you would have seen Western philosophical aesthetics in action: “Freedom of speech!” “An inalienable right!” “Don’t blame the movie!”

To argue otherwise, it was believed, was necessarily to argue for censorship of the artist—or worse, for the demise of good art.

In fairness, there was plenty of hypocritical handwringing among those who professed to defend Muslims against the so-called offensive speech of the “Innocence of Muslims.” These were the kinds of arguments that we would unfortunately never hear in defense of outraged Christians who feel, legitimately or not, that Michael Moore, Bill Maher, Chris Ofili, and Martin Scorsese have harmed the Christian faith.

Christians would inevitably be told to quit being hypersensitive babies.

Ross Douthat, in a New York Times article, “It’s Not About the Video,” was thankfully a welcomed voice of reason on this account. And to put his point somewhat simply, it’s never just about a video; it’s rather about the cross-cultural circumstances in which a video is experienced.

As our typical American filmmaker conceives it, the transaction that occurs in a dark theater is ultimately one that takes place between individuals: between the largely autonomous maker of moving images and the viewer of moving images. If the individual artist is true to his or her inner vision, the reasoning goes, society will benefit from the result.

This kind of approach to art is what James Davison Hunter calls a cultural “given.” It’s an unquestioned assumption that hides in the subconscious thinking of a society, and, as the case may be, it is also a dangerous sort of assumption precisely because we remain blind to it.

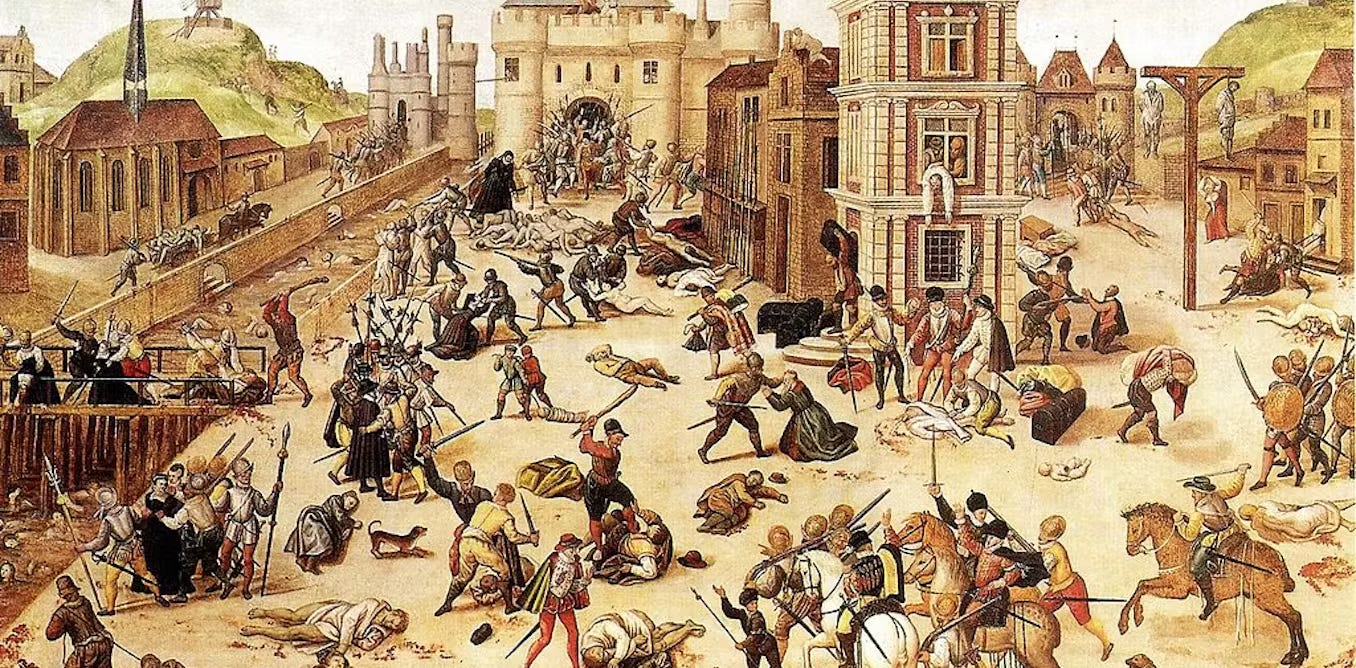

The curious thing, of course, is that this construal of the relationship of artist to society is the exception rather than the rule in human history. From the patristic era to the Medieval Age, and from the century of Reformation to the early years of the American Republic and beyond, Christians have treated images as powerfully charged, invoking and provoking violence, and they have known that their use or non-use affects the welfare of an entire society. They have also known that the responsibility for their relative use was a social one, not a solitary one.

The French author Marie-Jose Mondzain asks:

“Can images kill? Do images make us killers? Can we go so far as to attribute to them the guilt or responsibility of crimes and offenses that as objects they couldn’t actually have committed?”

History provides plenty of answers to these questions.

In the sixteenth century, Protestant reformers stripped altars bare and defaced liturgical paintings which they felt had corrupted the true worship of God. The Swiss Reformer Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575), in the spirit of Old Testament prophets, termed this activity “war against the idols.” Those who refused to forsake such images were beaten, flayed, hung and burned.

Twentieth-century monuments to Vladimir Lenin and Mao Tse-Tung, representing a history of violence, were torn down.

Spike Lee’s movie Do The Right Thing (1989) was accused of being both an act of violence and an incitement to violence.

In 2012, Warner Brothers cut all gun references in the trailer to The Dark Knight Rises after the Aurora, Colorado, shootings.

In 2024, pundits worried that Alex Garland’s movie, Civil War, might incite an actual civil war between red and blue states. Reported Justin Klawans for The Week:

Even if there aren't complete armies fighting on either side, "militia groups are also preparing for a dark future," Sam Jackson, a senior research fellow at the Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism, said to Politico.

Writing for The New York Times, Lisa Lerer adds this observation:

The top reason viewers cited for seeing the movie was not an interest in independent cinema or action films but the “political dystopian story line.” The interest in political chaos tracks with a growing body of research showing a dramatic uptick in public fears of violence.

Those fears seems to be well-founded:

Forty-nine percent of adults said they expected violence from the losing side in future elections, in a poll conducted by CBS/YouGov this year. And a survey by The Associated Press found that majorities of both Democratic and Republican adults said American democracy could be at risk depending on who won the next election.

But Barbara F. Walter, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego, who is the author of How Civil Wars Start, offers this sober note:

“This notion that America could never have a civil war; we’ve already had a really, really big one. There’s a sense of naiveté, of innocence, that we’re too good for that sort of stuff. We’re not.”

Finally, in his review of the movie for Vulture, critic Bilge Ebiri argues that the problem isn’t images that inspire violence but images that inure us to violence:

Beyond the plausibility of war in the United States or the tragedy of such an eventuality, it’s about the way we refuse to let images from wars like this get to us. It’s more a call for reflection, an attempt to put us in the shoes of others, than a warning — not an It Can Happen Here movie, but a Here’s What It’s Like movie. It doesn’t want to make us feel so much as it wants us to ask why we don’t feel anything.

Can images kill? Yes. Human history proves this point again and again.

Do images “cause” people to kill? The answer to this question is an ambiguous one.

Did the 1974 Hollywood disaster film The Towering Inferno inspire the terrorist authors of the destruction to the Twin Towers? Possibly, but not certainly. Is it the responsibility of filmmakers to guard against these kinds of violent responses? It all depends on what we mean by “guard against.”

If it is true, as the critical theorist W.J.T. Mitchell suggests, that the life of images is not a private or individual affair but rather a “social life,” then perhaps we need to ask ourselves basic questions about the mutual relationship between artist and society. While such questions cannot be easily resolved, I believe our assumptions need to be continually interrogated.

What kind of questions might we ask ourselves? Perhaps these, for starters:

What might result if filmmakers invited their community to participate not just with the final product’s marketability value but also with the whole process in which a film is made, from conception to reception?

What benefit might be had if filmmakers listened with and to the regular sorts of people which comprise their lives, trusting that their imaginations would be all the better for it?

How might the practices of the Christian church—such as breaking bread together and prayer, acts of service and social reconciliation—inform the aesthetic habits of filmmakers?

In short: What would it look like to conceive of the artist not in opposition to society, not as an outsider at odds with society, but rather in fellowship with those who bear with and for the well-being of the artist, without any softening of the irritating contours of good works of art?

David Morgan, in his book Icons of American Protestantism (1996), writes: “An image is never simply what an artist says it is but is also what the artist’s training, publisher, dealer, market, audience, and critics say it is.”

An image, in other words, is what a society says it is.

It’s important that we be able to to imagine a society that grows in its capacity to respond thoughtfully to moving images alongside artists, who, in turn, might welcome the opportunity to be deeply implicated by that society.

(This post is an adaptation of a previous essay via The Curator.)

Well put! There's a lot of work that still needs to be done regarding the ethics of the artist, especially if, when and how an artist ought to practice self-censorship. I really appreciated your suggestions about artists engaging with their communities. Thank you!