On Art & Suffering

How artists help us to name the pain of our lives.

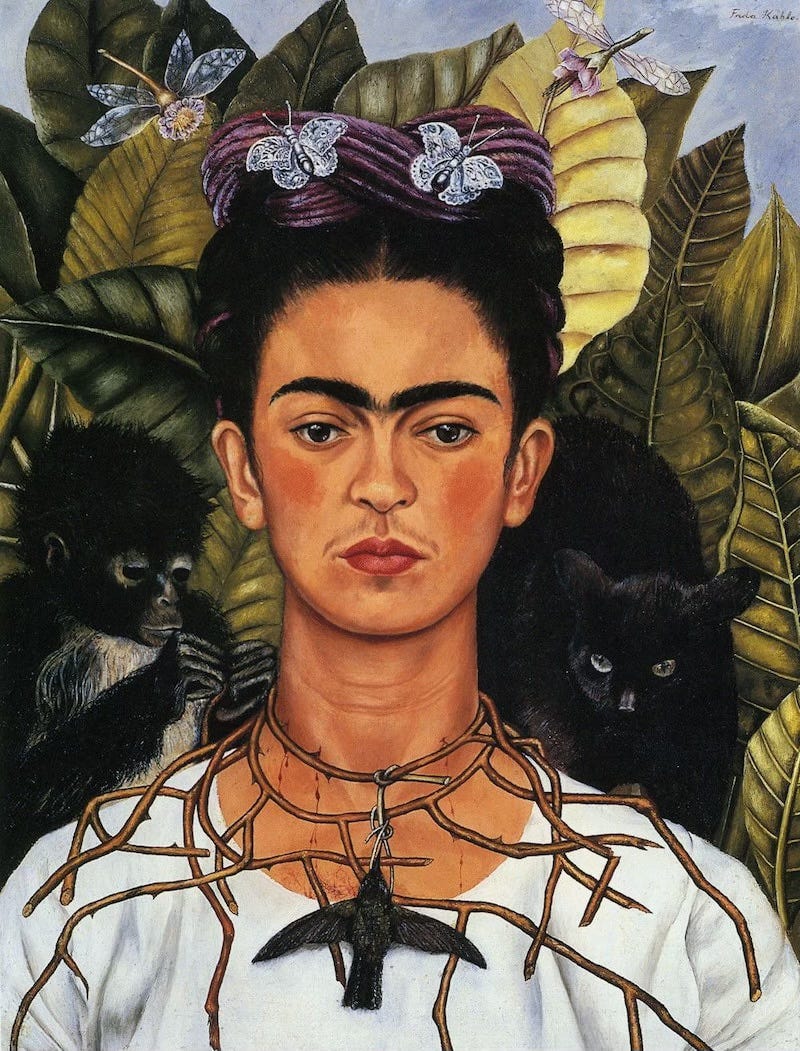

In her 2002 film, Frida, Julie Taymor, noted for her exquisitely visceral and brightly colorful movies, recounts the life of the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). The Frida we encounter in Taymor’s telling is a fiery, indomitable figure despite her many setbacks.

Early in the film, Frida suffers from the effects of polio as a child and then, at eighteen, is severely injured in a bus accident that fractures her pelvic bone and punctures her uterus, robbing her thereby of any chance to bear children. This represents only the beginning of a lifelong struggle with pain.

Brought to life in an Academy Award-nominated performance by the actress Salma Hayek, Frida aims to make sense of the many traumas of her life through art.

The experience of multiple miscarriages, a struggle with alcoholism, recurring bouts of marital unhappiness, depression, loneliness, chronic pain, and the amputation of her right leg due to the spread of gangrene through her body—all of these afflictions served as the context in which she produced some of her greatest work, in a style that has been described as naïve surrealism and magical realist.

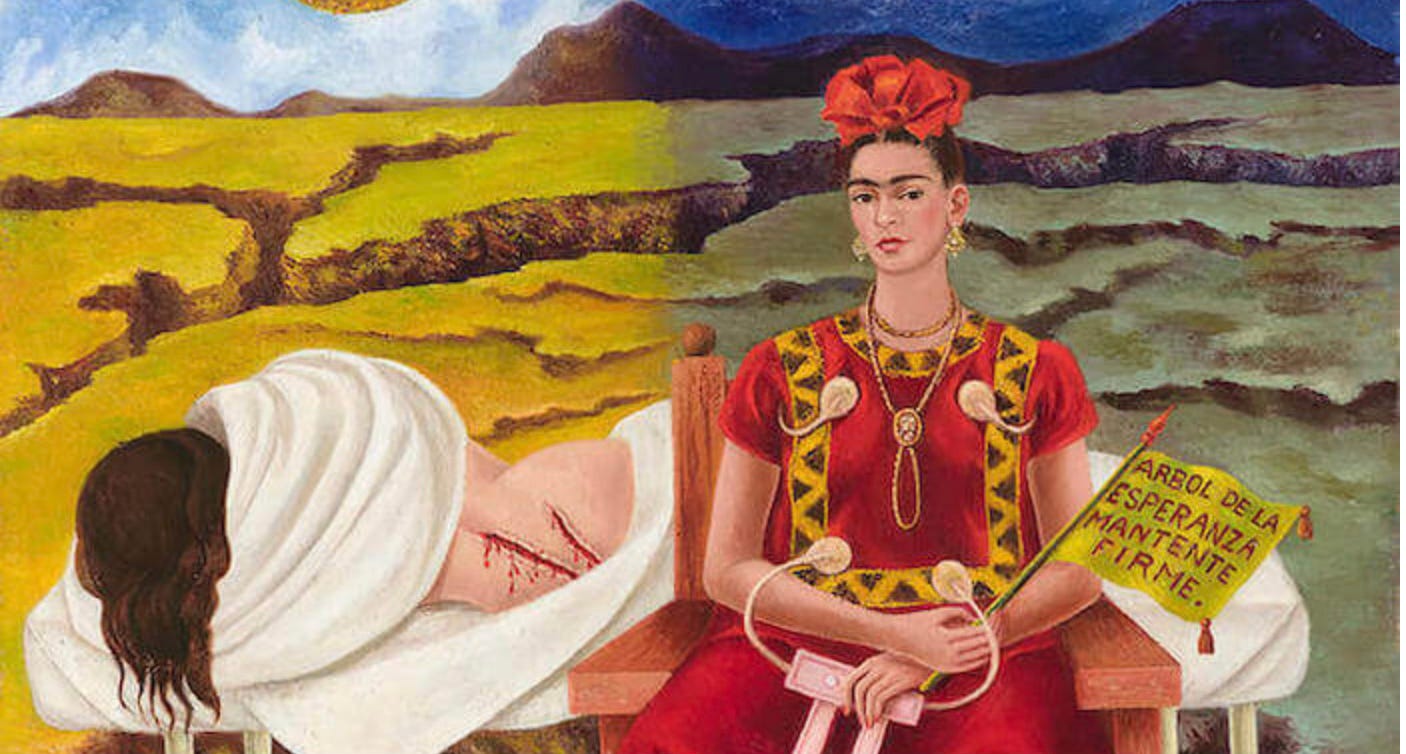

Her paintings from this period of life include The Broken Column (1944), Without Hope (1945), Tree of Hope, and The Wounded Deer (1946), each a visual testament to the torment of living in a profoundly broken physical body.

Experiencing in her flesh what she called “centuries of torture,” at one point in the movie, Frida turns to Diego Rivera, her off-and-on-again husband, and bitterly quips, “I want you to burn this Judas of a body. Burn it.”

Pain, for Frida, served as the cantus firmus of her life.

In the final months of her life, Frida spent most of her free time drawing skeletons and angels in her diary, an ominous portent of her imminent death. Her last entry in her diary records these words: "I joyfully await the exit—and I hope never to return—Frida."

She died at the age of 47 on July 13, 1954.

Less famous in life than posthumously, and struggling constantly to make a living from her work, Frida nonetheless became, according to the Tate Modern, one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century, the first Latin American artist to break the one-million-dollar threshold with the sale of her painting, Diego and I, and so beloved by her home country that, in 1984, they declared her works part of the national cultural heritage.

In the US, she became the first Hispanic woman to be honored with a postage stamp, and seventeen years later, in 2018, Mattel unveiled a new Barbie doll of Kahlo in celebration of International Women's Day.

One of the reasons for Kahlo's popularity, as the art critic John Berger sees it, is owed to the fact that "the sharing of pain is one of the essential preconditions for a refinding of dignity and hope" for many in our society, especially for those who may find themselves on its margin.

In Kahlo’s life, art and anguish are intimately and integrally related. In Frida, Alfred Molina’s Rivera describes her work thusly: “Her work is acid and tender; hard as steel and fine as a butterfly’s wing; lovable as a smile, cruel as the bitterness of life. I don’t believe that ever before has a woman put such agonized poetry on a canvas.”

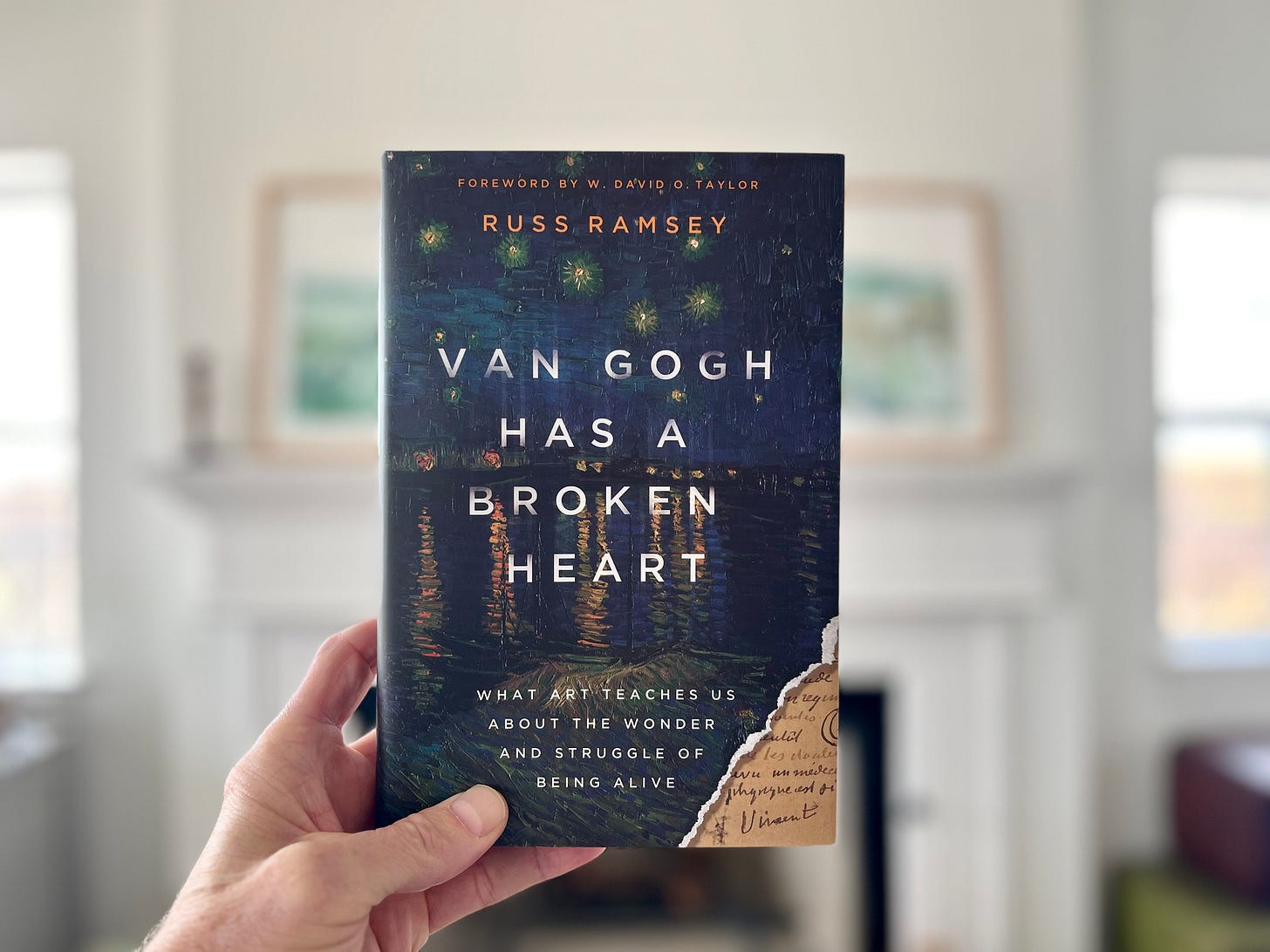

“Art shows us back to ourselves,” writes Russ Ramsey in his book, Van Gogh Has a Broken Heart: What Art Teaches us About the Wonder and Struggle of Being Alive, “and the best art doesn’t flinch or look away. Rather, it acknowledges the complexity of struggles like poverty, weariness, and grief while defiantly holding forth beauty.”

This is a story, he argues, that needs to be told, because it is far too easy for us to perceive our suffering as a kind of failure in life rather than as a means of grace—as an obstacle to get over and around as quickly as possible rather than as occasion for the broken beauty of Christ to be slowly but surely formed in us.

“Why are we so drawn to sad stories?” Ramsey wonders out loud, homing in on the heart of his project. We’re drawn to them, he answers, because they prepare us for what’s coming. “They remind us,” he writes, “that we are not alone in our pain.”

Such stories “tell us that these sorrows we experience, which can leave us feeling so isolated, are, in fact, well-traveled roads.” While Ramsey’s book isn’t a sad book, it is nevertheless a book full of sad stories. Why does this matter, in particular for those of us who may feel a pressure to ignore them or to get through them as swiftly as we can manage?

It matters, Ramsey explains, because this “is where much of the world’s art is born—from struggle and sorrow.”

Artists, as Ramsey shows us throughout this poignant work, are especially equipped to prepare us to face our own struggles with humility and to feel our own sorrows deeply without being undone by them, and to feel the possibility of hope, not just on the other side of our sorrows but also in the very middle of them, as the trees that show up in Frida Kahlo’s paintings suggest symbolically.

In painting her sorrows, Frida Kahlo, nicknamed by her countrymen as la heroína del dolor, not only sought to make sense of the often-senseless in her own life, but she also made space for viewers to find their own tragic sorrows, seemingly irreparable losses, and various experiences of rejection or loneliness named and dignified.

Her life story gets retold on canvas and thereby becomes all of our story. Her pain becomes memorialized in pigment, line, texture, and color—and then again on the silver screen in Taymor’s Frida—and thus fixes before our eyes an image of the possibility of hope and wholeness.

If it is true, as Flannery O’Connor once wrote, that “a story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way,” then Ramsey gives us here a collection of stories—of Doré and Degas, of Gauguin and Gentileschi—that together convey a truth that can only be revealed properly in this way.

Through such stories, we discover how our sorrows are ultimately hallowed by the One who enters fully into the painful stories of our own lives in order to show us that our suffering matters, while also becoming the place from which the Spirit enables us to become agents of God’s healing grace to those who find themselves lost and alone in their griefs.

This is a story that never gets old, and it is one Russ tells beautifully throughout Van Gogh Has a Broken Heart.

And so goes my Foreword to Russ’ marvelous book, which I heartily encourage to buy and to read for yourself!

My only concern with the art of suffering is that it becomes very difficult to critique the art on aesthetic grounds. How can one critique the record of another person's trials? Kahlo shares much stylistic and iconographic concerns with surrealists such as Salvador Dali; but Dali's art is objective and universalist in a way that Kahlo's can never be. There is a tendency to read the life stories of artists into their works, and this is a good thing, to an extent; but when an artist's story becomes more important than the art itself (which, I would argue, has happened in Kahlo's case), the art gains but also loses.