“Imagination is morally required because we refuse to allow the ‘necessities’ of the world, which are often but stale habits, to go unchanged or unchallenged when they are in fact susceptible to the power of imagination.”

– Stanley Hauerwas, “On Keeping Theological Ethics Imaginative”

The imagination is the gateway to empathy. This is a fact that artists know firsthand, that Jesus assumes in his parables, and that Christians ignore at their own peril.

Typical of an artist’s sense of things is actress Cate Blanchett’s observation in a piece she wrote for The New York Times, in May of 2020, that art “matters because it lets us engage with our complex social fabric, allowing us to cross divides and work toward a safer and more meaningful existence together.” In teaching us about one another, she adds, art has the capacity to inspire “empathy rather than anger.” Or hate. Or prejudice. Or, worse, indifference.

The film critic Roger Ebert once quipped that movies, at bottom, are “empathy machines.” When we watch movies, he writes, we can walk in another’s shoes, see what it feels like to be a different person, or race, or class, to live in another time or to believe otherwise about the world as we know it. Such is the case, for example, with movies like “Inside Out,” “Schindler’s List,” “The BFG,” “Hidden Figures” or “Slumdog Millionaire.”

The same goes for other media of art, as with, for instance, “A Raisin in the Sun,” by Lorraine Hansberry (theater), “Frankenstein,” by Mary Shelley (literature), “Bluey” (TV), “The Potato Eaters,” by Vincent Van Gogh (painting), or “Kindness,” by the poet Naomi Shihab Nye. From Nye’s poem:

Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.

The clinical psychologist Joe Behen, who serves as the Executive Director of Counseling, Health, and Disability Services at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, notes how “Artists, as a whole, are more empathic than non-artists….They tend to have more permeable personal boundaries that allow them to connect to people in meaningful, emotional ways. That connection provides fuel for the creative process.”

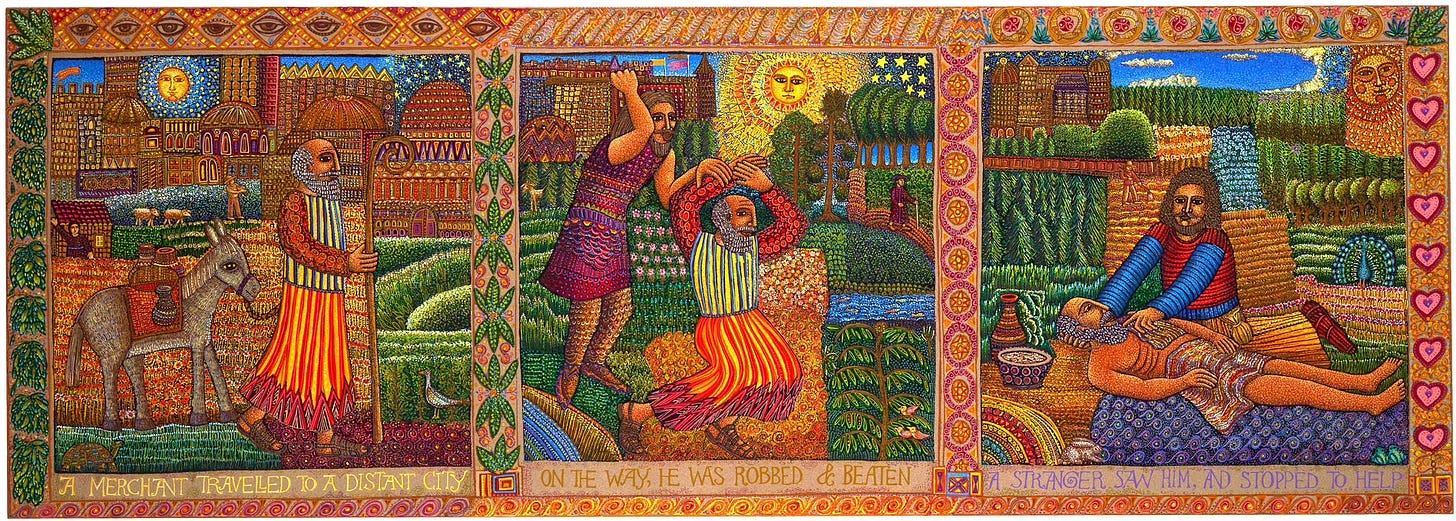

Jesus, on this account, is the quintessential artist. In parable after parable, the un-imaginable becomes imaginable and neighbor love is made more plausible in the face of seemingly impossible obstacles.

In his parable of the Good Samaritan, for instance, Christ draws his listeners, graciously but also cleverly, into a narrative that subverts prevailing assumptions about a faithful life. He does so by pulling the lawyer affectively into a plot, as I write in my book, Glimpses of the New Creation.

The plot, in turn, involves an “aha” moment, where the lawyer sees the answer vicariously but really. The lawyer not only sees the truth, as it is played out in Jesus’ narrative, he also feels true neighborliness, as it is exhibited in the Samaritan protagonist. A twist occurs in the story and the lawyer finds himself implicated in a role that he might never have imagined for himself: playing the “bad guy” instead of the “good guy.”

In what ways might we take advantage of the gift of artists to help us re-imagine the good news of neighbor love in these trying & troubling times?

We could no doubt preach about “baptized imaginations” as it relates to neighbor love, but we might also give our eyes something to look at, such as Indian-Australian Frank Wesley’s “Forgiving Father” painting or contemporary iconographer Kelly Latimore’s “Tent City Nativity,” and trust that this experience of seeing might help us imagine the radical love of Christ to the least, the last and the lost.

We could pray about the nations, but we might also but we might also give our people a chance to feel by watching The Bible Project’s video on the significance of “The City” in the Bible or projecting images from Jordan Raynor’s book, “The Royal in You.”

We could exhort our people to forgive those who have hurt us or we could let them contemplate an image of forgiveness on a poster in the foyer of the church, such as Scott Erickson’s painting, “Forgive Thy Other,” or Kreg Yingst’s “Prince of Peace.”

We could read the story of the Good Samaritan but we might also invite our people to see an image of Arely Morales, “Una por una” (One by One) exhibit, or Swedish-Mexican John August Swanson’s “Good Samaritan” painting, or Joel Schoon-Tanis’ whimsical story, “Why Is My Nayber?”, on the bulletin or in a e-news letter, and thereby strengthen our “fellow feeling” muscles.

And, lastly, we could talk about the goodness of bodies, but we might also ask our people to consider the work of the Azerbaijani artist Rauf Mamedov, “The Annunciation (Seven Bible Scenes),” or Tim Lowly’s painting, “Temma on Earth,” and wonder whether our ideas of goodness extends, as it does with God’s ideas, to those with physical or intellectual disabilities.

My point is this.

Art offers us an invaluable opportunity not only to re-imagine ourselves as the limbs of Christ’s very Body in the world—his hands and feet, his eyes and ears, his mouth and heart to neighbors and strangers—but also to re-imagine our ecclesial family lines and loyalties, stretching across the globe and down through the centuries, which, as the New Testament sees it, supersede our blood lines and cultural loyalties.

I end here with a prayer “For Being the Limbs of Christ” from my book, Prayers for the Pilgrimage, which Jon Guerra put to music a couple of years ago at a Laity Lodge retreat:

Incarnate God, Word made Flesh:

Use my hands, I pray,

To bring a healing touch to those

whose bodies are in pain this day;

Incarnate God, Word made Flesh:

Use my feet, I pray,

To bring a word of peace to those

who are at war with themselves this day;

Incarnate God, Word made Flesh:

Use my mouth, I pray,

To speak a word of hope to those

who despair this day;

Incarnate God, Word made Flesh:

Use my ears, I pray,

To be hearing ears to those

who need to come clean this day.

Incarnate God, Word made Flesh:

Be pleased to be

My hands and my feet

My eyes and my ears

My mouth and my tongue

To be a messenger of your own Body this day.